|

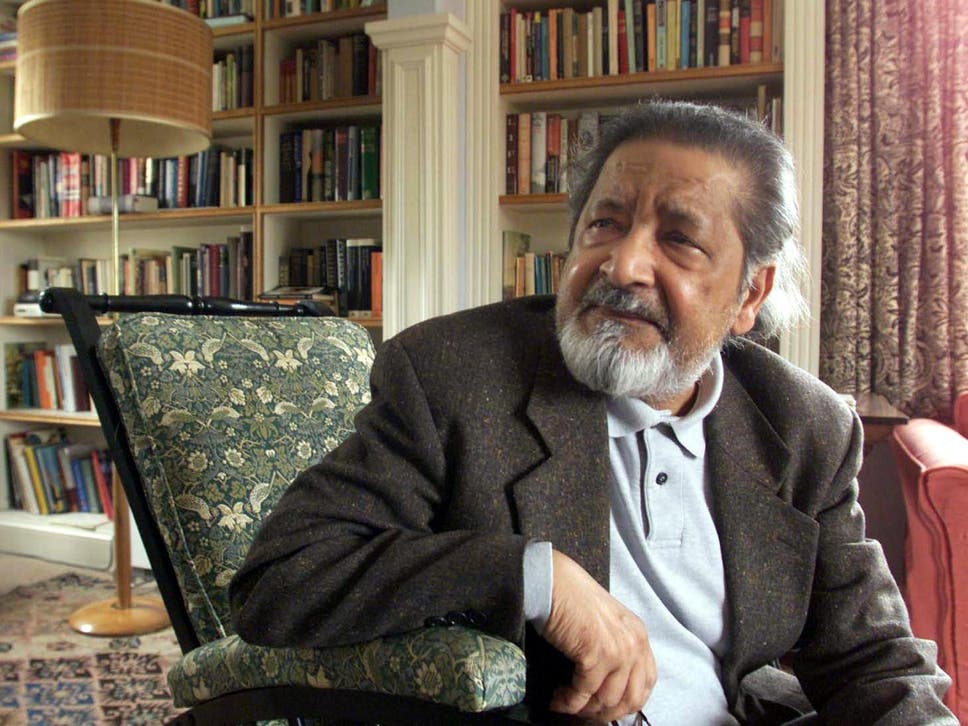

| V. S. Naipaul |

Although I'm not a Naipaul fanatic, I 've probably read a dozen or more of his books, and enjoyed every one of them. But Naipaul was more than a novelist, and wrote a number of fascinating books describing the places, people, and cultures he encountered during his extensive travels. His observations, opinions, and conclusions often surprise, and sometimes irritate, but always force me to examine my own attitudes and judgments. Some critics, of course, objected to his cultural characterizations and plastered him with negative labels, apparently hoping that some might stick. He's been called a racist, a misogynist, an Islamophobe, a Hindu nationalist, and more...I've always thought of him as a man who told the truth as he saw it. Can we ask anything more of a writer than this?

If you haven't read Naipaul, by all means do so. I especially enjoyed his semi-biographical novel, The Enigma of Arrival, as well as his much earlier work, A House for Mr. Biswas. Among his non-fiction works, I suppose my favorites include Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey; The Middle Passage; and A Turn in the South.

If you haven't read Naipaul, by all means do so. I especially enjoyed his semi-biographical novel, The Enigma of Arrival, as well as his much earlier work, A House for Mr. Biswas. Among his non-fiction works, I suppose my favorites include Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey; The Middle Passage; and A Turn in the South.

My bookshelves house 10 volumes of Naipaul's works and, coincidentally, they reside on the same small shelf with about a dozen of Evelyn Waugh's books. Despite their widely varied backgrounds, the two men had much in common. Each could be included among the best writers of his time. Each wrote wonderful novels, often based on his own life experiences. And each wrote exceptional works of non-fiction describing his travels in culturally distant lands.

Interestingly, both Waugh and Naipaul have also been described as personally irascible, as curmudgeons with few close friends. I can't and won't judge another based on his personality, assuming that what we see of another is rarely an accurate reflection of his true self. Anyway, I would much rather have a handful of close friends who accept me for who I am, than be surrounded by a flock of chirping, faithless acquaintances who come and go with the seasons.

Interestingly, both Waugh and Naipaul have also been described as personally irascible, as curmudgeons with few close friends. I can't and won't judge another based on his personality, assuming that what we see of another is rarely an accurate reflection of his true self. Anyway, I would much rather have a handful of close friends who accept me for who I am, than be surrounded by a flock of chirping, faithless acquaintances who come and go with the seasons.

Religiously the two men were far apart. Although Naipaul often criticized the religious values held by many today, particularly among those who practice Islam, I don't know if he were a man of faith. One can certainly be personally unpleasant and still be an active believer. After all we are all sinners. Evelyn Waugh, of course, was a convert to Catholicism. Once, when asked how he could justify his nasty disposition with his Catholic faith, Waugh replied, "You have no idea how much nastier I would be if I were not a Catholic. Without supernatural aid I would hardly be a human being." Waugh, too, was a man who spoke the truth as he saw it.

Rest in peace, Vidia, and thank you for your work that caused so many to reexamine the world in which we live. May God shine His face upon you...